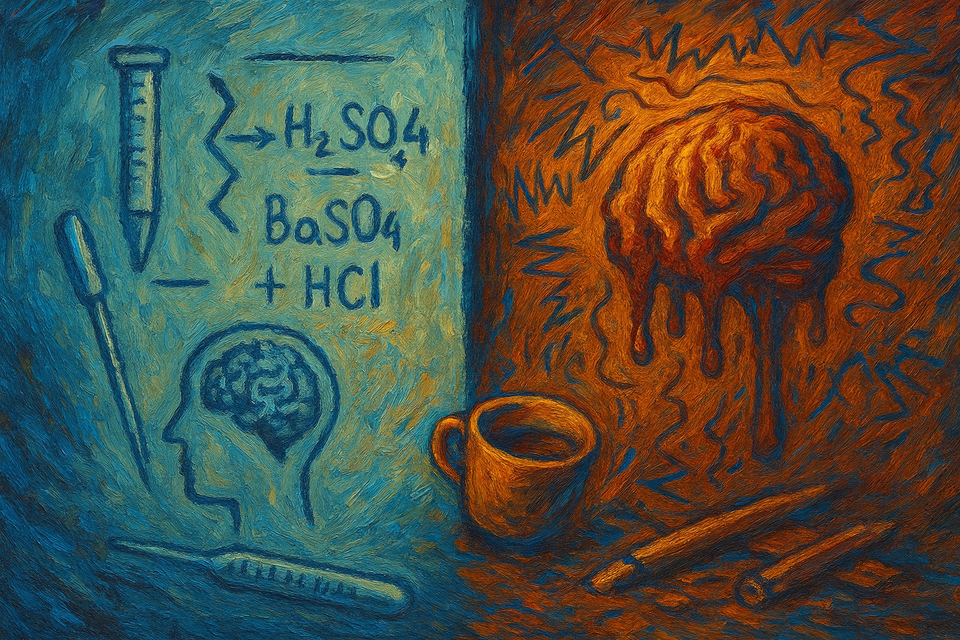

The Scientific Method and The Emotional Damage: A Tale of Two Feelings

Researchers are people of science, of facts, of specifics. With the duty of being unbiased, they set their assumptions aside and prioritize what the data tells them above everything else. And yet, when that son of a Reviewer 2 criticizes their data… Oof, man… Tough blow.

More than just “a job”

Scientists pour years of their lives and their sleep-deprived brain power into planning, experimenting, analyzing, preparing, and presenting. That is true dedication and commitment to the work.

This makes it so, as all researchers know, work ends up not being “just work”. At some point, working in science becomes, I dare say, part of the identity of a researcher.

Should it get that personal?

Probably not. But, ironically, that exact fusion is what keeps many researchers going.

The truth is that that fusional relationship between work and personal value is what gives researchers the drive for perseverance and continuous pursuit of the truth.

I’m not saying in any way that this is healthy, since many many many many (enough?) times it isn’t. But in the end, that passion for science is the fuel that gives researchers' combustion engine brains the power to keep pushing.

A personal attack

So when a paper gets rejected, a grant ends up in the bin, or someone drops a harsh comment at a conference, it doesn’t feel like they’re criticizing ‘your work’ anymore. It feels like they’re questioning you.

Science may be objective, but doing science is clearly not.

The Vulnerability of Creative Work in Research

If you allow me, my dear reader, I am now going to compare science to art.

I know, it’s a little presumptuous. But let me be.

Research is creative work. Maybe not with brush strokes, but with ideas. And ideas are personal.

So if you painted an (arguably) beautiful landscape and I arrive there and just say it sucks, your heart is probably going to hurt a bit.

That way, rejection hurts personally because it feels like someone rejecting your ideas and your imagination, not just your data.

The Identity Fusion Problem

Good Results ≠ Competence.1

You can be a great researcher, and still have an experiment designed to cure cancer end up showing no significant results.

Are you a bad scientist then? No.

Is it easy to make this distinction? Also no.

Peer Review as an Emotional Gym (and Therapy?)

Since it is so personal for your work, overcoming rejection ends up being a little bit like grieving. And maybe, to overcome this, you need to go through different stages of grief:

Denial – “Maybe the editor got the manuscripts mixed up”.

Anger – “Reviewer, who can go f@%& , clearly didn’t even READ the methods!”

Bargaining – “Maybe if I show them one more Western Blot they will see it…”

Depression – “Why don’t I just give up and open a bakery?”

Acceptance – “Time to resubmit to another journal and pretend I’m fine.”

And maybe in the meantime you should also reflect about why that matters so much to you and why that specific “no” hits so hard.

Is it because that acceptance was meant to compensate for that time that those kids didn’t want to play with you in recess?

How was your relationship with your father?

Oh, I’m afraid we will have to end it here for today. See you next week.

1 - And this one, from my experience, is a fact that tends to be forgotten the more senior researchers become.

Comments ()