The perils of low hanging fruit

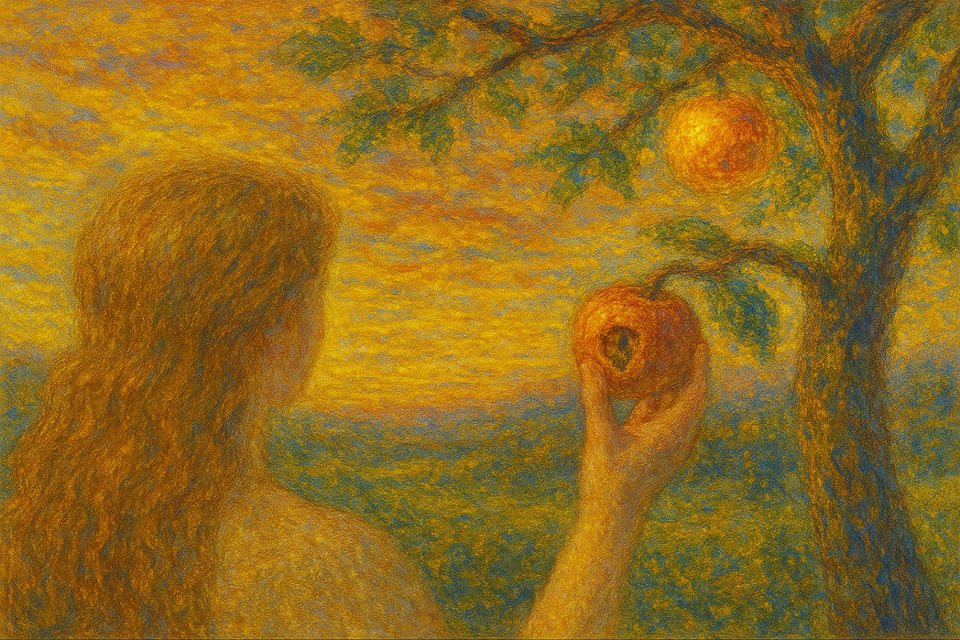

The first time I heard the expression "low hanging fruit" in science, I got excited. Simple projects that seem to be straightforward – seemingly untouched by other scientists. Projects you could pluck right off the tree and bite into, reaping the succulent fruity juice of success. In three months it would be wrapped up. An easy publication. Nobody could blame Eve if those were the promises…

After a few years in research, however, I am realizing that my excitement for those sorts of projects was not based in scientific endeavor. More so, I came to realize that it is a symptom of the modern academic system itself and that the appeal of these easy projects says less about curiosity — and more about survival.

I started a PhD because I enjoy understanding things. Being honest, that is the main reason I went into science and am fascinated by the natural world. Understanding. How can humans investigate the world around us in a methodical manner and derive conclusions that update our understanding our reality? Today, this has even gone beyond just simple understanding. We are now trying to manipulate, control, and create new innovations that cannot exist in a natural setting. Innovative materials, new molecules, large language models. Some of the things we have developed have gotten so complex, we are even reapplying old-school science to try and understand our own creations. But understanding the world — or creating a new (hopefully better) one — takes deep knowledge and time. The opposite of a "low hanging fruit".

I have heard “low hanging fruit” be used (and have used it) to describe a wide number of projects from those that seem “easy”, and those that have already been started but left in a drawer to those that are deemed safe and will most likely yield good results. It is obvious why it might feel tempting to take over such a project. After all, why struggle your way through the thorns when someone’s already halfway up the tree or the project is easy? It’s comforting — the project roadmap is sketched, straightforward, and with a few experiments, the publication within reach.

But the “low hanging fruits” exist in our minds because the system doesn't really allow you to take your time. "Publish or perish" is sadly a reality. Who wouldn't go for the low hanging fruit? Quick publications keep your name on the radar. And when institutions reward quantity over quality, it becomes a numbers game. A game that doesn’t necessarily care whether you deeply understood what you were publishing about — only that you did. This pressure not only devalues slow, meaningful work but pushes early-career researchers to prioritize output over curiosity. And once you're in that mindset, it's hard to reconfigure. And I speak from experience.

I also wonder, do we actually learn as much from low hanging fruit projects? Or is their existence already a self-fulfilling prophecy limiting what we can obtain from the project? Sure, in the best case they get us a publication. But does the approach stretch our minds, force us to rethink assumptions, or change how we actually tackle the next question? Maybe for some people, but maybe not. Sometimes they’re glorified protocol exercises — follow these steps, tweak one thing, apply this method, measure the outcome. There’s value in execution, of course. But if science is about understanding, questioning, discovering — then reducing it to a library of predictable publishable outcomes might slowly erode the curiosity that brought us here in the first place.

So what if we took low hanging fruit out of our vocabulary? Imagine aiming for the “high hanging fruit” that you can’t see that clearly but might be even more succulent? It seems like a great endeavor but the system does not directly reward it. What if your project needs a bit longer? What if it does not work? Especially, your work does not happen in isolation and it is hard not to compare yourself — to the postdoc next to you publishing a paper every few months, or the PhD student one year younger getting their first first author out before you. Is it a mistake not pursuing those easy fruit? Trusting your own process, your own pace, requires constant reminders and a lot of fighting self-doubt. Honest feedback helps. Having mentors and colleagues who ask why you're doing what you're doing, and not just when will you publish it, makes a world of difference. It’s okay to feel behind — but it’s also okay to take the time to build something you're proud of and answer questions you find interesting. Not all growth is visible.

Low hanging fruit are not all bad. If it’s a pertinent scientific question, then it clearly does merit investigation. Sometimes the simplest questions are the most elegant — and the most overlooked. A quick wrap-up project can also help you get going, especially when you’re stuck in the mud of a long, uncertain experiment. Finishing something, anything, can give you the momentum and confidence you need to tackle those riskier, high-hanging goals. But those projects should be just that: fuel, not the whole feast. If your entire research diet is made of low hanging fruit, you might fill pages — but not necessarily expand your horizons. The danger lies in letting ease become habit. In the long run, the deeper questions — the ones that take a bit longer to unravel — are the ones that nourish the soul of science.

So, when anyone offers you or tempts you with a "low hanging fruit", take a moment to check it out before plucking it off the tree. Check for worms or a rotting branch, and do not be afraid to pass it off and focus on those higher up. They might take more time to get to, but most likely will be worth the climb.

Comments ()