Predatory journals mirror the flaws in academic publishing.

How to catch a predator in the academic publisher quagmire.

Dear esteemed Professor Waltho,

I would like to take the privilege to invite you to contribute your research/discoveries to our overly open access journal. Simply email your manuscript as an attachment to below email...

This is a typical opening from one of countless spam emails that flood the inboxes of scientists worldwide every day.

Ordinarily these often grammatically incorrect, excessively flattering messages go straight into my spam inbox, soliciting an amused chuckle from me at most. However, recently they piqued my curiosity.

Who are the journals behind these emails? How bad are they? And what do they say about our publishing system?

The shadow behind open access publishing

With the rise of open access came a new world order in academic publishing. Readers could now read articles without paying a subscription fee, opening up scientific research to basically anyone with internet access. However, behind this incredible win for knowledge transfer came the rise of predatory journals.

The term ‘predatory journal’ was first coined by the librarian Jeffrey Beall in 2010. In a 2012 commentary in Nature, he describes such journals as those that "exploit the author-pays model of open-access publishing for their own profit" without providing proper editorial and publishing services.

Beall compiled a list of over 900 "potential, possible, or probable predatory” publishers. Although this list was taken down in 2017, it remains accessible through independent archives and is still a widely used resource to identify predatory publishers. On the other side, ‘whitelists’ have been developed to recognise reputable open access publishers, such as the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

The most prevalent open access model, and that which predatory journals exploit, is ‘gold open access’ in which authors pay an article processing fee. Referring to gold open access, as compared to the subscription-based model, Beall stated

“authors, rather than libraries, are the customers of open-access publishers so a powerful incentive to maintain quality has been removed.”

Rather than quality for the subscription-paying readership, the journal is now incentivised by the desires of the fee-paying author.

Publish (with a predator) or perish

One would hope that quality and scientific rigour are also top priorities for researchers. But in today’s ‘publish or perish’ academic culture, the pressure to produce papers may outweigh the pursuit of excellence. Publishing has become not just a scholarly endeavour, but a means of securing jobs, promotions, and funding. Compounded by tight timelines and the financial burden of author fees, particularly for researchers in lower-income countries, author's priorities could favour fast, affordable publication over rigorous peer review.

To find out more about what predatory journals are offering potential authors, I replied to 15 unsolicited manuscript requests that I received from journals on Beall’s list (pray for my inbox as it may never be free from spam again!). I received responses with promises like publication ‘within 21 days after submission’, ‘75% manuscript acceptance rate’ and a ‘20% discount’ on author processing fees.

One would hope that those evaluating the quality of scientists’ research would be able to detect poor quality work in predatory journals. However, an Italian study, which looked into the evaluation of scientists for professorships, found this wasn’t always the case. Evaluators were encouraged to assess quality by publication number using a whitelist of supposedly reputable journals, in which the study's authors found predatory journals from Beall’s list. Evaluators with themselves weaker research credentials were more likely to pass researchers who had published in predatory journals.

Scientists go undercover

When I emailed journals asking for more details about their publishing process, the responses I received claimed adherence to standard practices - plagiarism checks, double-blind peer review, and the provision of metrics (impact factors) and indexing numbers (ISSNs and DOIs).

Impact factors reflect how often articles are cited from a journal in a given year. Legitimate impact factors are provided by the global analytics company Clarivate for journals in their Journal Citation Reports. The journals that I emailed were not part of this whitelist, and therefore their impact factors are not legitimate. ISSNs and DOIs are like IDs for journals and articles, respectively, helping with tracking and citation. They do not say anything about the quality or legitimacy of content.

I reached out to 31 scientists whose names appeared as authors or editorial board members in journals flagged on Beall’s list. Predictably, I only received four replies - two declined to comment, one was content with their publication, and the fourth offered a glimpse behind the curtain. That scientist, who wished to stay anonymous, explained to me that they had been tricked into accepting an editorial role, mistaking the journal’s name for that of a reputable one (think “Journal of X” vs “The Journal of X”). Upon realizing their mistake, they had tried to have their name removed, but never heard back, nor received any editorial duties despite still being listed as an editor. This is just one example of foul play, other investigations have uncovered far more widespread and systematic malpractice.

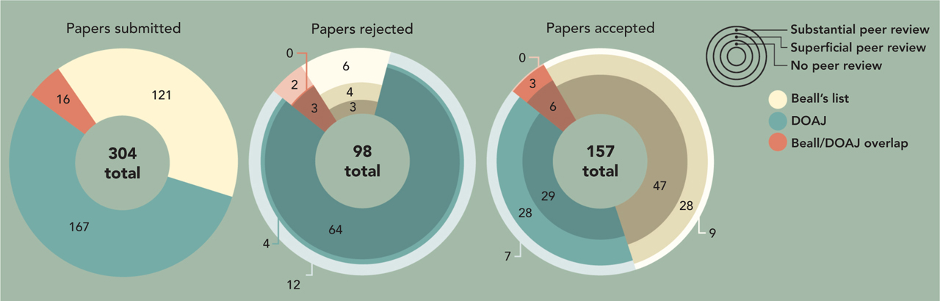

In 2013, scientist and journalist John Bohannon submitted a fake scientific paper with glaring flaws to 304 fee-charging open access journals, both those from Beall’s list and the DOAJ whitelist. 157 of these journals accepted the bogus paper, including 73 journals from DOAJ.

Amazingly, Bohannon’s investigation contributed to the first and only lawsuit from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission case against a publisher. The publisher in question, OMICs, was ordered to pay a fine of over $50 million.

A similar investigation was done by a group of Polish psychologists in 2017. In this case the team created fictitious academic, Dr. Anna O. Szust (hilariously Oszust is the Polish word for fraudster), and applied for editorial positions at 360 journals from Beall’s list and whitelists from DOAJ and Journal Citation Reports. Despite having no qualifications, she was accepted by 48 journals, primarily those listed on Beall's list, but also some listed on DOJ.

Both investigations reveal gaps in Beall’s lists and bad practices of journals in whitelists. This raises the question of how good are we actually at identifying predatory journals, and how do we define them?

Definitions: reviewing the review

In 2019 a group of international experts came together to pin down a clear definition of what makes a journal "predatory", published in Nature. But what made their conclusions especially fascinating was that, in the process, they ended up highlighting systemic issues in academic publishing as a whole - problems that ironically make it even harder to distinguish predatory journals from legitimate ones.

For example, they listed “lack of transparency” and “deviation from best editorial and publication practices” as separate criteria with the reasoning that

“transparency in operational procedures (such as how editorial decisions are made, fees applied and peer review organized) is presently somewhat aspirational in academic publishing and thus cannot be considered a current best practice”.

Similarly, they omitted "quality of peer review" as a factor for assessing predatory journals as “many legitimate journals fail to make their peer-review processes sufficiently transparent”, therefore making it “too subjective”.

Echoing this, the scientist I spoke to, who was wrongly listed an editoral board member of a predatory journal, protested when I defined such journals as those "that prey on scientists, overcharging them for publication without rigorous peer review or editorial process". He responded with “lousy peer review process is often found even in reputable journals”. This suggests that opaque publishing processing causes mistrust.

Mirror mirror on the wall, how do we stop enabling predatory journals?

If the academic environment continues with its publish or perish evaluation pressure, there will always be a market for predatory journals. And if publishing processing and reviews remain opaque, they will continue to use this opportunity for malpractice.

We need to rethink the way we measure scientific success - reducing the reliance on publication counts and impact factors. Several initiatives have emerged to promote more holistic and meaningful evaluation methods, including The Leiden Manifesto which promotes qualitative evaluation, and Altmetrics which also considers factors like social media mentions and policy document citations as a measure of impact.

To allow us to evaluate paper quality and promote trust in a journals, we need a more transparent publishing process. Some publishers, like eLife, F1000, and PeerJ, either routinely publish peer review reports alongside the paper or give authors the option to do so.

Research quality can also be evaluated by the broader research community even after peer review using the platform PubPeer, where anonymous commentors can add comments to published articles.

Diamond open access publishers remove the financial burden on the author, by providing publication without any fees. These publishers are typically funded by universities, research institutions or scholarly societies, and are also listed in DOAJ.

Predatory journals hold up a mirror to academia, exposing and exploiting the flaws in its publishing culture. They should prompt us to reflect on and strive for positive change.

Comments ()