Law & disorder in academic publishing

Impact factor. The power of this term is unparalleled in academia. The word “impact” by itself is already so profoundly heavy.

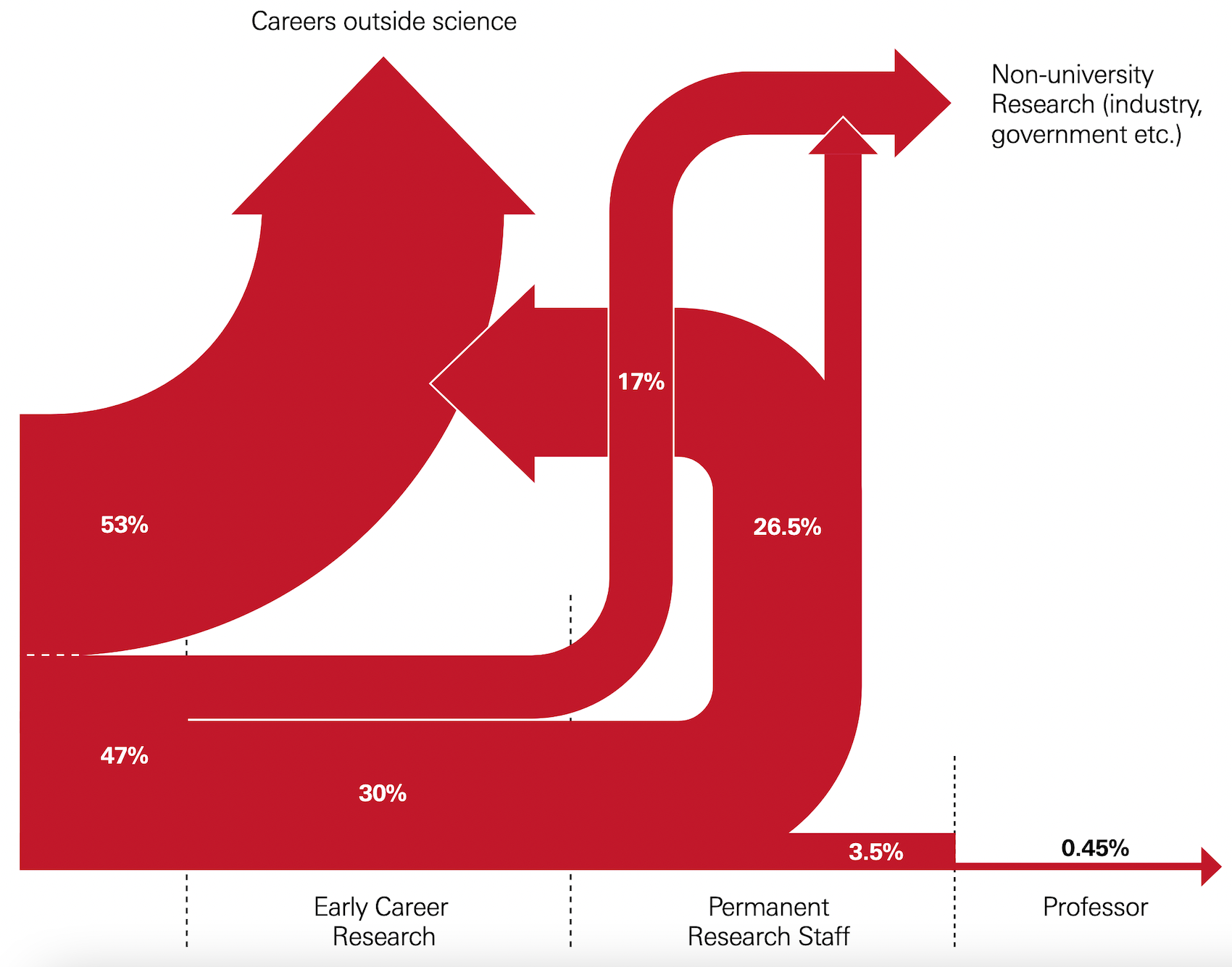

And second in line to it, would be tenure. I put it in second place, because less and less early-career researchers are aiming to get faculty positions (they must have seen this graph↓).

It may seem strange to an outsider, but journal impact factors and tenure are concepts that are intertwined in academia and this has become somewhat of a curse that researchers cannot get rid of.

Academic merit is tied to the journals in which you publish. Inventions and discoveries are quantified.

There have been attempts to move away from this type of metrics-led evaluation, namely with the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA). Do people actually follow it? Do they take into consideration all the different ways a researcher has contributed to the scientific community or the general public?

Sometimes. But not nearly as much as they should.

A journal’s impact factor ≠ the value of a researcher

Let’s step back for a second to understand what an impact factor is. A journal’s impact factor is determined by a corporation named Clarivate, it is updated every year and reflects the average number of citations of the articles that have been published in that journal in the last two years. I’m sure you can see how a small number of highly cited papers can completely skew the impact factor. It’s therefore completely wrong to base the value of an article on the mean of the citations of all the other articles published in the same journal.

The impact factor of a journal is not a measure of any single article, let alone a researcher. As such, it has no business gatekeeping academic opportunity.

I will not go into any more details about the inappropriate use of journal impact factors, but I urge you to read an in depth explanation/outburst. You may think the author is being too hard on the reader but the message sticks.

Goodhart’s law and the publishing game

In some countries, publishing a paper or four (no joke) is a requirement to graduate and to get the PhD title. Quantity prevails over quality.

If becoming a tenured professor is dependent on publications, then researchers will play the game. They will aim to publish, not to just do research.

According to Goodhart’s law, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. So, is the number of publications a good measure for academic success?

Here is a quote from a professor complaining 30 years ago:

“[...]with the pressures for tenure, recognition, a lot of people just want to produce a lot of papers rather than concentrating on putting out a few high-quality papers. The journals are loaded with papers. There’s just too many papers-not only from those who don’t have tenure, but from those who do in order to get grants, etc.” (Professor of physics at a private research university) (source)

Too many papers in 1995.

Let’s see how that number changed since then:

It tripled.

And if we check the number of articles in scientific journals per millions of people in the world, there has been a 121% increase since 1996.

Seems to me like the measure became a target.

Gresham’s law and the pollution of the scientific record

In the professor’s quote, one key point to consider is that the alternative of “producing a lot of papers” is “putting out a few high-quality papers”. Not doing research.

According to Gresham’s law, if there is “good money” and “bad money” circulating out in the world, “bad money” will always take over the whole system. This law considers that both currencies are equivalent in value. Still, people will always prefer to spend the “bad money” and keep the “good money” safely tucked away in an undisclosed location. Here is a 1-minute explanatory video for you digital generations.

This applies very well to the academic publishing system nowadays. Let’s say there is “good research” and “bad research”.

Good research is when you do research because you are curious about something and you want to expand the knowledge in that area. Maybe your goal is to understand a biological process or to cure a certain disease. This means that you will most likely work on it until you have a breakthrough. Probably, you will also make sure that you are certain about the validity of your findings before sharing them with the world.

Bad research is when you want to publish as many papers as possible, as fast as possible. This means that you will most likely focus on p-values, prioritize experiments that you know will satisfy the peer reviewers who will judge your work, and come up with extravagant titles for your papers.

And for both good research and bad research the outcome is the same: you publish a paper. The good and bad research currencies have the same value.

In a system that values quantity over quality, and even paper over no paper, this leads to the gamification of scientific knowledge production and publication.

Would anyone reading this be able to say that they never once thought about what the reviewers will say about your upcoming paper while you are still doing the experiments? Have you ever kept an experiment aside because you knew that question would come during the peer review?

Bad research already took over.

Are we ever going to get some order around here?

This requires collective action. So far, there have been attempts but the timing was never ideal. I believe things will change when the new generation gets the final word. Even though they might seem unfazed by life sometimes, if their future is threatened, they do revolt.

We, the researchers, are uniquely placed to reclaim our academic identity and to detach it from misleading metrics.

Numbers should not be used to define professional worth.

We are not paper machines.

Comments ()