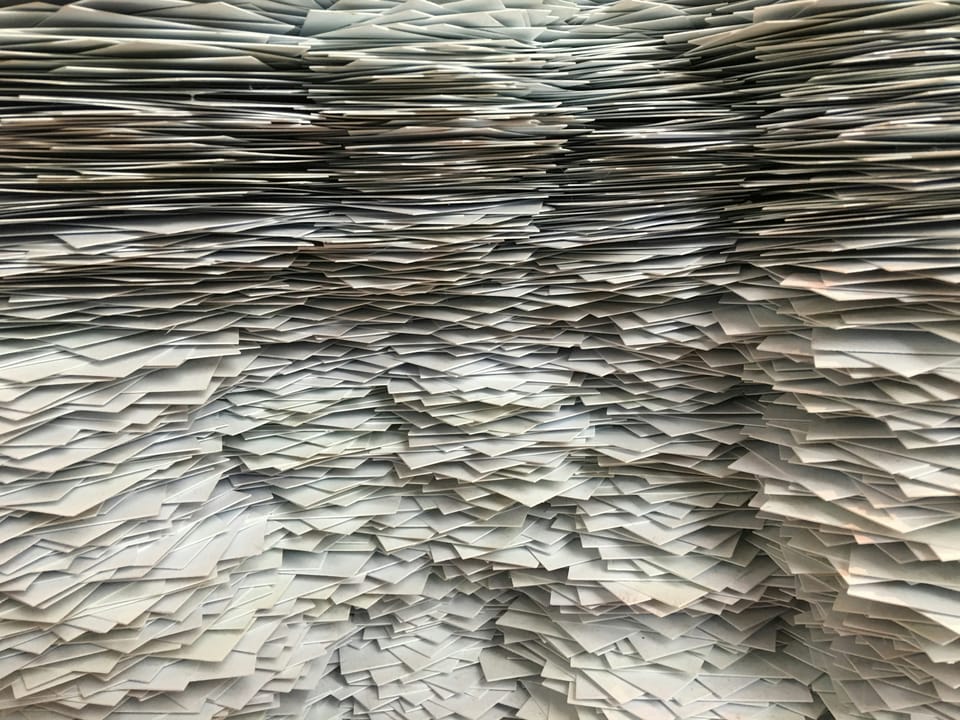

I’m a scientist and we’re publishing too much

The first step of alcoholics anonymous is to admit you have an addiction (or so the many TV shows tell me). Well, I’m a scientist and science has an addiction. It’s an addiction that every scientist has, and no it isn’t the immense feeling of being the first to discover something new, or the crippling imposter syndrome. It isn’t even that all-too-real alcohol dependency that we seem to acquire. As with many addictions, it’s one that we have a love-hate relationship with. In small doses it would be great but things have gotten out of hand. We’re addicted to publishing. And this isn’t even entirely voluntary, we are forced into this addiction.

And things are getting worse, much worse.

Quite simply, we are publishing research that isn’t adding to or advancing our knowledge. We are publishing sub-standard work that is rushed out, just to increase our citation counts or number of publications in pursuit of grants and jobs. “Salami slicing” of data is a common term used to describe the dividing of a single study into multiple smaller studies, simply to inflate a researcher's publication record. Some scientists are even fabricating work or turning to paper mills, causing significant damage to trust in research.

But how did we get here?

There is no singular route that led us to this addiction, but rather a combination of things. From the perverse career incentives to questionable policies and abusive business models.

Career incentives

Academic assessment has become about one singular thing - papers. In the words of Metallica, nothing else matters. Where you publish and how much you publish are the currency of academic careers. Impact is measured in the number of articles you have published in journals above a certain impact factor and how many citations your work has received.

But what if you’ve published some work that had a huge impact on government policy? Or you’re an exceptionally talented teacher? Maybe you’re an amazing science communicator. Sorry to tell you but academia just does not care. Even securing funding is heavily tied to your past publishing record.

These incentives result in researchers playing the game and submitting to the publish or perish culture. We cut our stories into “publishable chunks” just to have more papers under our names. We might even rush or fabricate work, if the right intense pressure is being exerted. This is bad for science. Bad for society. There’s a reason there are so many declarations that have changing career incentives as a focus.

Graduate programs

Across the world, many doctoral schools require students to publish a set number of papers in specific journals before they can graduate. This is effectively a way of passing the burden of assessment onto peer reviewers rather than a viva voce. This also forces an influx of studies that may not be the highest quality or that are salami-sliced to meet arbitrary criteria instead of one big, complete, story.

There are even institutions that force students to cite work from that institution in order to graduate; another questionable research practice.

This also places a huge pressure onto graduate students who must discover positive results. We can probably all empathise with how much negative data a thesis produces too. This adds unnecessary pressure to these students, in addition to pressure on an already broken peer review system.

Medics

Just as many graduate programmes require publishing to graduate, many medical appointments and career progression pathways also require publishing. This is very similar to the requirements with graduation in that these medical appointments require staff to publish a certain number of papers in journals that are above a particular impact factor threshold.

Journals and the Open Access movement

Traditional publishers bear a large amount of responsibility for the current system. The companies that own academic publishers also own a vast swathe of the research ecosystem - from discovering new work to grants to research assessment. This control has helped to keep the focus of assessment on journal brands, proxies such as impact factors, and publications. These companies also own the “league” tables that rank universities and are relied on by universities to attract international students, and therefore income.

Between 2019 and 2024, journals made over $12 billion in profit (yes, you did read that correctly; billion, with a B). This has been made possible thanks to the open access movement which resulted in the creation of the APC business model. This has gone on to create a system that prioritises volume over quality, flooding the literature with poor quality studies.

This system is a natural evolution of that created by Robert Maxwell after the second World War. He described academic publishing as a “perpetual financing machine”. He would be so proud of the current iteration.

I want to break free

This time borrowing the words of Queen, “I don't need you, I've got to break free”. But how? Well, I’m not actually in academia any more so where I publish doesn’t matter. But what about you, dear reader? How do you break free?

Collectively we need to work together to change the incentive structures. If you sit on funding or hiring panels then you can directly influence this change. If you don’t, then support the oh so many declarations and lobby your PI’s, department heads and institutions to actually adopt the principles of these. You don’t need to resort to poor proxies to judge a new recruit or decide who to fund (in fact lotteries are much fairer in this latter point).

The requirement to publish to graduate is entirely unnecessary and causes increased stress for students. Institutions should move away from this, either replacing publications with preprints or removing the requirement entirely. For the medical career path, a similar replacement could be made.

Ultimately, we must break free from the stranglehold of journals. The best route to achieve this is through preprints. Preprints place the focus back on the content and science, instead of poor proxies. This helps us to switch back to sharing high quality work rather than salami-slicing or low quality work that doesn’t add to our knowledge.

Comments ()