ChatGPT et al.

The rise of Large Language Models in academic writing.

Postdoctoral researcher Dr Verena Haage was reviewing a manuscript for a reputable neuroscience journal when she began to notice unusual inconsistencies.

“The abstract sounded exciting and the introduction was written in perfect English. However, soon after I started reading the results section, I realised something was off,” recounts Haage.

Haage noticed that some figures had strange proportions, or illogical experimental timepoints, and that figures were arranged in a senseless order. Additionally, she found many sentences that, while grammatically correct, made no sense in the larger scientific context.

“After scrutinising the whole manuscript, it was clear it was completely generated by AI,” says Haage.

The final confirmation came when she looked up the authors; the supposed first author didn’t exist, the listed last author had no connection to the stated institution and their linked ORCID profile had only been created few weeks before submission.

This was a textbook case of AI misuse in academic writing, and a shocking reminder of how far such a paper can get in the review process before being caught.

But Haage’s story is only one extreme. With the current boom in ChatGPT and similar tools, it’s estimated that thousands of papers now include some degree of AI support - from simple proofreading to more substantial text generation.

So what are the implications of AI use in academic writing? And how can researchers use these tools ethically and responsibly?

How ChatGPT 'grew its brain'

Let’s take a quick look at Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and how they came to be.

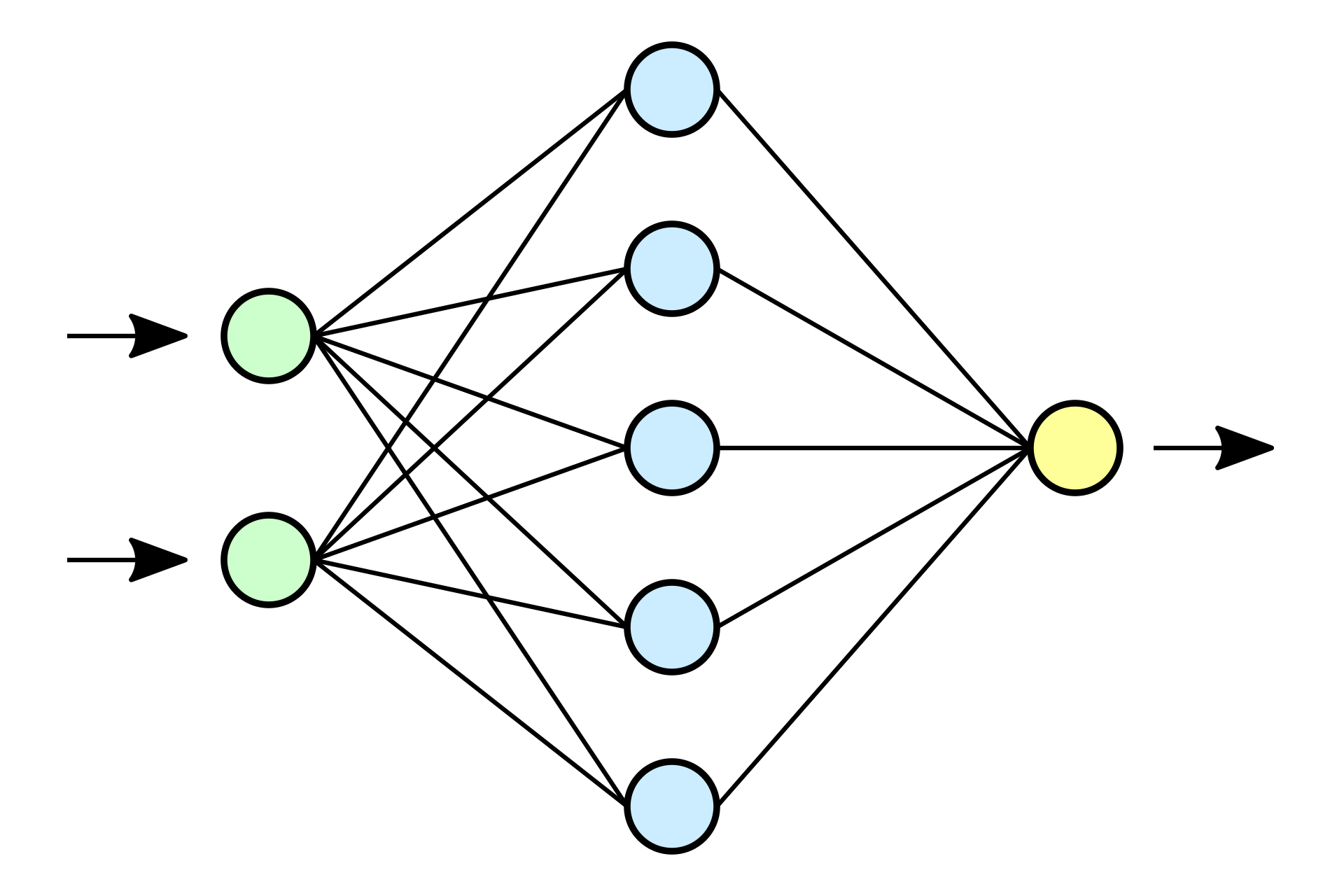

Over the last decades, natural language processing models have been developed and used by computer scientists for tasks like language translation. Like our brains these models use a neural network - nodes connected in an structured architecture.

The real revolution came in 2017 with the introduction of a new neural

network architecture - the Transformer (the T in GPT). Combined with training

on massive datasets of text with ever-larger number of parameters, this led to the creation of LLMs.

At their core, LLMs are trained to predict the next word in a sentence. With enough data and clever fine-tuning, this word-prediction trick turned into the ability to generate fluent, human-like responses to almost any text prompt.

Reinforcement learning and the design of a chatbot interface led to the human-like conversations that millions of users worldwide now have daily with the likes of ChatGPT.

Your own personal translator and proofreader

LLMs have taken off for all kinds of writing tasks, from emails to meal prep suggestions. But what makes them especially appealing for academic writing?

My German colleagues always liked to remind me that many chemical elements carry German-derived names (Natrium for sodium, Kalium for potassium, and so on). But today in 2025, the language of science is unmistakably English.

This has long given native speakers like me an undeniable advantage when it comes to scientific writing. Now LLMs are levelling the playing field, not only for non-native speakers, but also for anyone who struggles with writing.

Still they must be used with caution.

“LLMs need to be seen and understood as supportive tools, but not as substitutes that can fully take over our scientific writing tasks,” says Haage.

She suggests that LLMs can best support targeted writing tasks:

“They are suited to, for example, drafting a manuscript introduction, after the author has developed their stream of thoughts and collected the milestone papers that they want to cite.”

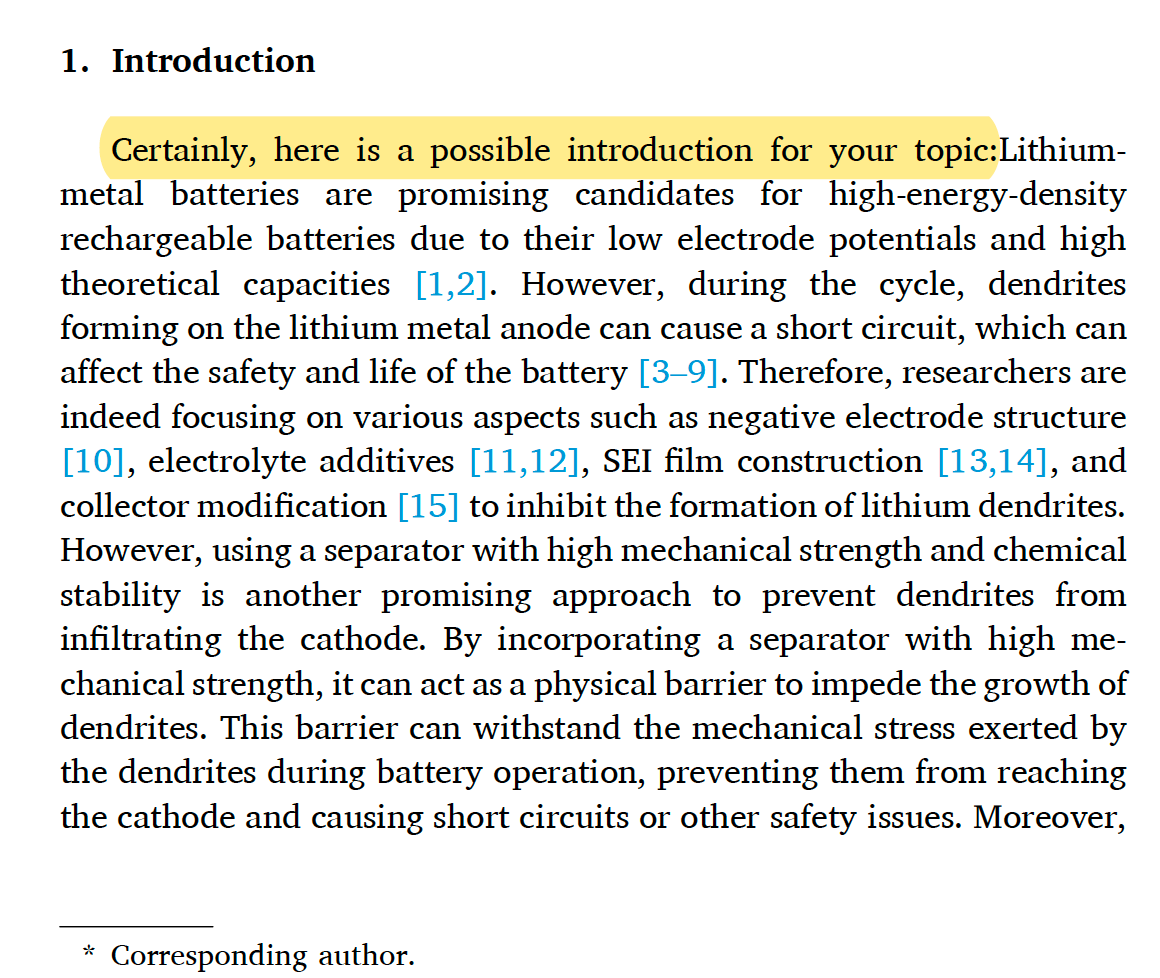

Proper citation is a key limitation. LLMs are notorious for generating references to non-existent publications, a phenomenon known as hallucination.

Equally important is human oversight. When I’ve used ChatGPT to edit my own scientific texts, I sometimes found that its “improvements” change sentences to the point where they are no longer scientifically accurate. Without careful review this could lead to the spread of misinformation.

From lab bench to submission at record speed

Even whilst factoring in the time required for quality control, LLM-assisted writing is much faster than relying on humans alone. But does this increased productivity translate into faster publication?

Haage is skeptical.

“Journals are often the bottlenecks,” she explains.

Along with already lengthy manuscript processing and review times, the introduction of AI-written texts makes it harder and more time consuming to assess paper quality. As Haage’s story shows, this burden can fall on reviewers.

“Journals will need to adapt,” says Haage, “Crucial will be implementing quality control mechanisms: the first screening will most likely be AI-based, followed by human assessment. In my opinion, this is the moment when journals have no other choice than financially compensating reviewers.”

Without such safeguards, paper mills and predatory journals could exploit AI to flood the field with low-quality or misleading research. The result would be an infodemic - a glut of unreliable papers that erodes trust in science and spreads misinformation.

The loss of skill and originality

LLMs are trained on existing texts and generate responses by predicting the most likely next word in a sentence based on this data. Some describe this as a form of auto-plagiarism because the generated texts inherently do not contain original thought and the original sources of information on which the texts are based are difficult to trace.

Lack of originality and creativity affects not just the text, but also the authors.

“Going through the process of developing your scientific story…is also a craft that needs to be learned and trained,” says Haage.

Over-reliance on LLMs, especially for idea generation, not just for proof-reading and formatting, risks dulling researchers’ skills in creativity, science communication and writing in general.

AI-policy and best practices

In this fast-changing landscape, journals have had to rapidly adapt their editorial policies to accommodate AI use without undermining ethics.

For example, in early 2023 the editor-in-chief of Science strictly prohibited AI use in manuscript text, images or graphics. Ten months later, the journal reversed course, allowing AI use on the basis of it being stated in the submission cover letter, acknowledgements and methods section.

The editorial policies of other journals vary slightly in the extent of AI use disclosure: Nature, for example, does not require disclosure of LLM use for “AI-assisted copy editing”.

One thing that all journals agree on is that AI cannot be an author. As Nature explains AI cannot effectively be accountable for a paper’s content. The principle of whether AI can meet authorship criteria was cautiously tested in a 2023 study.

In 2024, researchers from leading institutions published ethical guidelines for the LLM use in academic writing. This emphasised three essential principles: human vetting, substantial human contribution to the work, and transparency.

In an interview with the University of Oxford Magazine, study co-author Dr Brain Earp said:

“Ethical guidelines are not only about reducing risk; they are also about maximising potential benefits.”

Those words capture the need to prioritise safety and integrity, as we move forward on the exciting applications of AI in academic writing and beyond.

/This piece was edited with the assistance of ChatGPT. All content was reviewed and revised by me for accuracy and clarity.

Comments ()